In 1970, the anthropologist Carlos Alberto Ricardo embarked on a trip that would change his life: his first visit to the Amazon. After that, his work mapping the locations of indigenous groups became crucial to the debate around indigenous rights in Brazil, directly shaping Brazil’s 1988 Constitution.

It was during this time that Beto Ricardo, as he is more commonly known, helped start the Centro Ecumênico de Documentação e Informação (Ecumenical Documentation and Information Center – Cedi), which would later split into various civil society organizations, one of which was the Instituto Socioambiental (Social and Environmental Institute – ISA). At ISA, Beto currently coordinates the Rio Negro Program, which “promotes and articulates processes and partnerships to help develop a transborder strategies to improve the quality of life, promote social and environmental diversity, ensure food security and inspire collaborative and intercultural production of knowledge in the Rio Negro Basin.”

Ricardo is also the coordinator of the Rede Amazônica de Informação Socioambiental Georreferenciada (Amazon Network of Georeferenced Social and Environmental Information – Raisg), an initiative by civil organizations from the Amazon countries aiming to build a sustainable development program for the region.

For over 40 years, Beto Ricardo has stood out for his pioneering work integrating struggles for human rights, environmental protection and sustainable development in Brazil. His innovative solutions have safeguarded not only indigenous people’s legal rights, but also the protection of million of hectares of land and the tools to manage it in a sustainable fashion.

Believe.Earth (BE) – What is the scope and relevance of the Rio Negro Program?

Beto Ricardo (BR) – The Rio Negro Basin, in the northwestern part of the Amazon region, with 71 million hectares of land shared by four countries – Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela and Guyana – is a hotspot for the conservation and safeguarding of the Amazon’s social and environmental heritage. The Rio Negro Program promotes and articulates processes and partnerships to help develop a transborder strategies to improve the quality of life, promote social and environmental diversity, ensure food security and inspire collaborative and intercultural production of knowledge in the Rio Negro Basin. There are 45 indigenous groups there, along with two pieces of Brazil’s cultural heritage: the Iauaretê Waterfall and the Rio Negro Traditional Agricultural System. Besides our headquarters in São Paulo and an office in Brasília, [the capital,] ISA has regional offices in the Rio Negro Basin, in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Boa Vista and Manaus.

The Rio Negro Basin is composed, for the most part, of Indigenous Reservations and Units of Conservation, which are intensely well-preserved landscapes. These protected areas are part of the Amazon’s northern corridor, which runs from the Atlantic coast to the Andes, and encompasses Guyana, Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil, requiring transnational cooperation between those countries.

BE – Your relationship with environmental activism, indigenous peoples and sustainability goes back decades. What do you think is the role of NGOs in environmental protection in Brazil today? Are there fewer obstacles? And what about society’s awareness? Are we more aware and more active?

BR – My activism is guided by the social and environmental perspective that is in ISA’s DNA, since the group was founded in 1994 by people who had prominent roles in fights for social rights during the 1970s, 80s and 90s.

I believe Brazilian society today is more aware of the severity of the planetary crisis related to climate change. In this sense, the role of NGOs is very important, but not enough to bring about systemic changes. After the UN’s Rio-92 Conference, Brazil came to be seen by the international community as a country that is very diverse socially and environmentally. But the country’s political class has not embraced this vision. To sum it all up: Brazil is the only country in the world named after a tree which is on the endangered species list.

BE – In the book Povos Indígenas no Brasil (Indigenous People of Brazil: 2011-2016), you talk about the growth of the indigenous population and the number of indigenous groups in Brazil, but also the paralysis in the process of recognizing native lands during this time. How do you see these issues today?

BR – This publication is the twelfth volume in a series that began in 1980. Today Brazil has 252 indigenous ethnicities that speak over 150 languages. In the coming years, the indigenous population is expected to keep growing, whether because the fertility rate has increased in some tribes, or some previously-isolated tribes will become known to the rest of society, or even because some will reclaim their identity and become socially visible.

ISA maintains a monitoring team with a daily routine of entering information into a database organized by ethnicity and indigenous reservation. Along with articles by experts on issues related to Brazil’s native population, this accumulated data will be the basis for what we have nicknamed the Pibão, the publication we release more or less every five years, which serves as reference for both indigenous people and scholars, at the level of government, civil society and media. The latest one (2011 – 2016) was published last April. And the next one is being worked on.

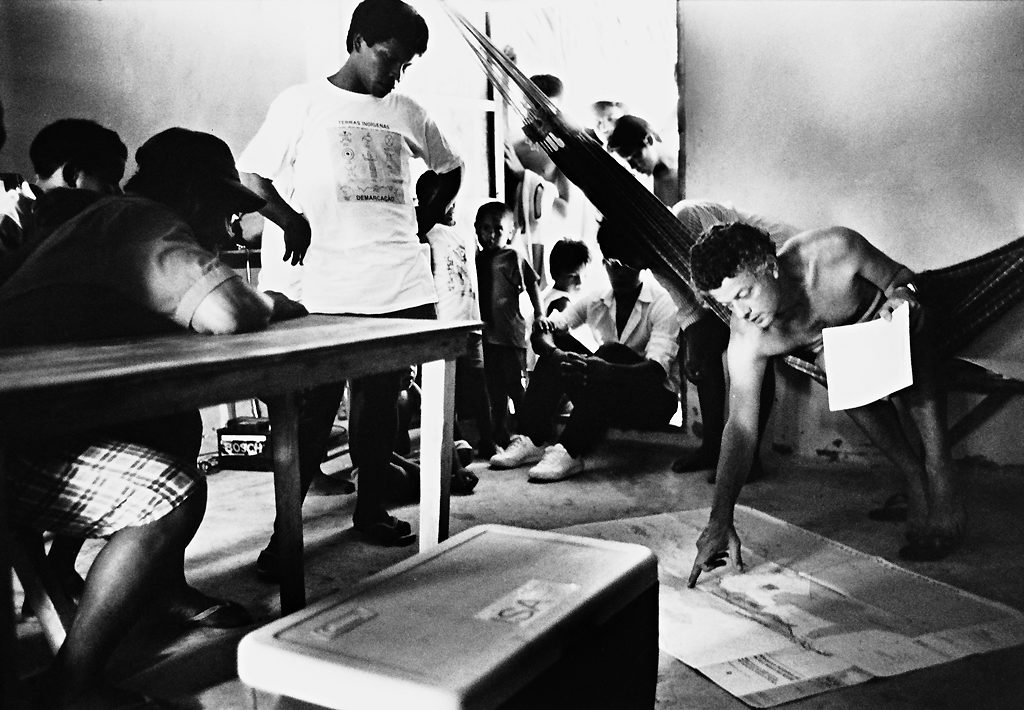

Beto Ricardo (in the hammock) during a meeting about the demarcation of indigenous lands along the Rio Negro, in the state of Amazonas (Pedro Martinelli /ISA /1997)

BE – You have said that society suffers from a “cyclical amnesia in relation to indigenous peoples.” How is it possible to raise awareness in our society on indigenous issues?

BR – We have to strengthen communication with society at large and launch smart campaigns, like the #MenosPreconceitoMaisÍndio [Less Prejudice Against Indians] campaign, launched by ISA in March of 2017, where we invited Brazil to look at indigenous people with greater generosity and respect, and less prejudice. The campaign was launched on broadcast and cable television channels, movie theatres and social media, and reached 22 million people in Brazil and around the world.

BE – Your work has been recognized and awarded internationally. What is the importance of this type of recognition and what impact have these awards had on your career?

BR – I was awarded the Goldman Prize for Latin America and Caribbean in 1992. I am very proud because the jury for the Goldman Environmental Foundation consists of activists linked to important causes. But in reality I have never touted this award publically. I work with indigenous people in the Amazon, and one of them taught me that we have to be discreet in life. Those who stand out too much individually become vulnerable to witchcraft.

BE – Do you believe in a sustainable future for Brazil and the world?

BR – I do believe in it. It’s like the use of seatbelts by car passengers in Brazil. For years there were campaigns calling for their use, but without success. Then, suddenly, everyone started using them. Children demanded them from their parents. They say we are living in the Anthropocene Era, where human action is the driving force behind the climatic changes that threaten the future of humanity. Check out the book The Ends of the World, by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Debora Danowski, published in 2014. This is why it’s urgent for us to adopt a social and environmental perspective on the planet.

Carlos Alberto Ricardo is an Ashoka fellow. Ashoka is a worldwide organization present in 84 countries and leads a movement in which any individual can be responsible for positive social transformation. This content is promoted in partnership with Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) and Greenpeace.

Published on 11/16/2017