This is a story about chaos, about a city whose blue sky often hides behind wide gray layers of air pollution and about an artist who dares to try to do something about it. Four years ago, Daan Roosegaarde, 38, a social designer and Dutch environmental activist, went to Beijing, China’s polluted capital, for a short visit.

From the top of a skyscraper on one cloudy day, Roosegaarde could not see the city through the window. “I felt like Beijing was trying to kill me,” says the artist and founder of Roosegaarde’s Studio, a Netherlands-based research lab exploring art, urban planning and the environment. “That day inspired me to create a project to fight air pollution,” he remembers, drinking some raspberry juice while sitting in his favorite coffee shop in the center of the Chinese capital.

Roosegaarde’s willingness to advocate for the cause resulted in the Smog Free Project, an initiative that brings together a team of scientists and designers engaged in the development of technologies to remove air pollutants. g.

The most famous of Roosegaarde’s team’s projects is the Smog Free Tower, an air filter seven meters high (23 feet) installed in open spaces. The first one was built in Beijing in 2016. Now, the studio is trying to expand the model to other polluted cities around the world, such as New Delhi, India; Medellin, Colombia; and Mexico City. The tiny particles of pollution collected during by the filter are compressed and turned into a stone that becomes a ring, which is sold for 250€ (almost US$ 250).

A ring made of pollution particles filtered from Beijing’s air by Roosegaarde’s Smog Free Tower (Photo: Roosegaarde’s Studio)

A study conducted by researchers from Eindhoven University of Technology in Netherlands found that the Smog Free Tower could reduce the atmospheric particulate matter (PM) within a 20-meter diameter of the tower by more than 45 percent . PMs are very fine particles of pollution that can penetrate the lungs and cause disease.

But a test conducted by the China Forum of Environmental Journalists’ staff suggests that the results may be less impressive. “We disagree about the results of this test, because it was not a scientific work. And I cannot stop pollution or change the current economic model by myself,” he says. “But, I can design public projects that mobilize the community and encourage government leaders to put sustainability back on the agenda. My role is to show that it is possible to create innovative solutions of great impact.”

A PRIVATE WORLD

Roosegaarde, who seems to live in a world of his own creation, has never tried to adjust to society’s standards. When he was in high school, he got a job in a bookstore because he wanted to read the classic writers of Russian literature for free. He sometimes missed the last train back home because he was so entertained by his readings. At times he slept among the bookshelves with Pushkin, Chekhov, and Nabokov. “School was very boring and that was the way I found to educate myself,” he says, smiling.

When he was 16, he had to choose a profession, but realized he wanted a type of work that did not yet exist. “I wanted to be an artist, a scientist and an entrepreneur at the same time, without giving up any of the three options,” Roosegaarde says. “I had to create my own world to get what I wanted.”

Before joining the University of Arts (AKI) in Enschede, Netherlands, Roosegaarde dropped out of two art schools because the hours of the traditional institutions made his overnight work impossible. AKI, however, was open 24 hours a day. He met scientists and engineers who confirmed one of his core convictions: “There is no shortage of money or technology to reverse environmental degradation, but there is a great lack of imagination,” he says.

Roosegaarde is determined to change the consumption model currently prevalent all over the world. “When the system allows pollution, the people who pay the price are those who want fresh air,” he says. The artist believes that the changes will happen first in China, because of the urgent need for change in that country. “China is the future, it is an innovative country and will lead the global sustainable development policies,” he says.

Smog Free Tower is a seven-meter high (23 feet) tower installed in Beijing that filters out some of the surrounding air pollution (Photo: Roosegaarde’s Studio)

LIFESTYLE CHANGES

It’s hard to breathe in Beijing. China has been the world’s largest carbon emitter, since 2007, when the populous Asian nation surpassed the United States in that ranking, and the Chinese people have begun to demand cleaner air. Coal supplies more than 80 percent of the country’s energy demand.

Many diseases, such as lung cancer, are associated with the inhalation of pollutants. In 2011 alone, particulate emissions from the burning of coal in China contributed to a quarter of a million premature deaths, according to Greenpeace. “In order to actually get good air in China, we need to do more than just improving the efficiency of air filters in public spaces,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, Greenpeace’s energy analyst for East Asia. “We need to shift the economic model towards sustainability.”

The health hazard of air pollution has influenced Chinese government policies. In his official speech at the 19th Communist Party Congress in October, President Xi Jinping said the word “environment” 89 times and “economy” 70 times, showing sympathy with sustainable solutions. The Ministry of Environmental Protection supports Roosegaarde’s initiatives in China.

AFFECTIVE ART

The newest innovation created by Roosegaarde’s studio is a mobile scrubber that can be attached to the millions of shared bikes in Beijing, beginning in 2018. The device is still under development, but the idea is that as particles of pollution pass through the scrubber, they are retained there, and fresh air is returned to the atmosphere. The innovation could encourage people to bike more and drive less, which would ease traffic jams and indirectly, reduce greenhouse gas emissions. For bikers, it offers the benefit of enjoying cleaner air during exercise.

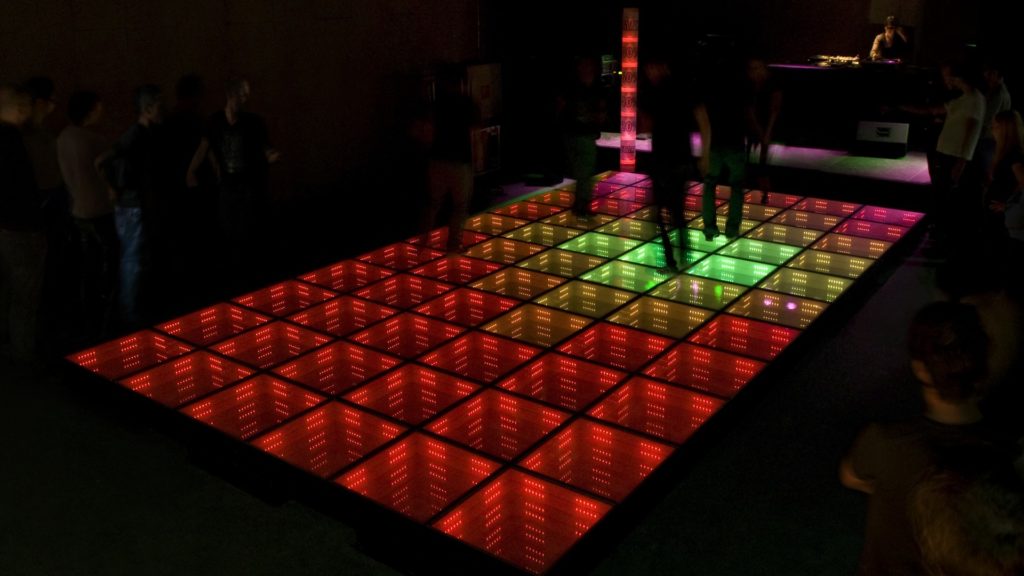

The sustainable dance floor created by Daan Roosegaarde takes advantage of the dancers’ movement to produce energy that lights the floor (Photo: Roosegaarde’s Studio)

Governments and companies interested in investing in social responsibility, and donors aligned to environmental and technological causes are the main financiers of Roosegaarde’s projects. Throughout his career, the artist has undertaken more than 20 projects, including a dance floor that generates energy. In the beginning, his work was more focused on technology and sensory perceptions. Recently, it has become more social, with an accompanying shift in venue. “I showed my work in art galleries, now I work with urban planners and use public spaces,” he says.

Integrating art with the environmental cause takes work. Daan Roosegaarde is a dedicated militant. Because he spends so much time working outside Rotterdam, the city where he lives, he decided to sell his house and car. “I’m a bit homeless now, which makes me feel free,” he says. His work takes him to Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Toronto, Singapore, Dubai, and London. “I start my day with dreams and end up with the pressure of perhaps not being able to handle everything,” he says. “But what happens when you put the pollution under pressure? It turns into a ‘diamond’,” he jokes, referring to the formation of the precious stone from carbon. It’s a fitting metaphor for Roosegaarde’s ongoing project: the transformation into art of material that many see only as a problem.