Learning about black peoples’ roots, understanding their historical influence, identifying with their own ancestry, setting an example to others wanting to study this history. These are the goals behind the “Study Cycle on Afro-Brazilian History and Cultures,” held annually by 3rd-year high school students at the Colégio Técnico Industrial de Santa Maria (CTISM) in the southern Brazilian city of Santa Maria.

It all began during class, with a question from a student who didn’t understand why all the city’s historical monuments honored white men. Other students then noticed that even the streets were named after aristocratic white men. The project started in 2010 and, each year, the students have made new discoveries and strengthened their own cultural identity.

“Our teacher proposed the project, and we embraced the idea of finding our roots and showing that we are significant, that we have a history, that we can research it and identify with it,” explains Ana Flávia de Oliveira Dutra de Souza, 17, who worked on the project in 2017.

“This year we researched 15 African kingdoms. We discovered their importance to Brazil, and how Africans came to Santa Maria, what culture they brought, and how they influence the city to this day,” says Gabrielle Sanger de Oliveira da Conceição, 18.

During their studies, the students also found that Santa Maria has many societies for black people. de Souza recalls this discovery with amusement: “When I got home, I told my father about these black societies and he said he’s a member of one of them. I was surprised!”

CHANGING THE COURSE OF HISTORY

The students conduct research, visit the city’s historical streets and monuments, and talk with the city’s black community. They then share what they learned during presentations at the school, which are open to the public. “We start with an introduction by black activists from the city, who talk about their experiences and how they fight for the cause of civil rights. After that, we present our research,” explains Jackson Marino da Silva Moraes, 19.

Among the important figures discovered by the students is the activist Nei D’Ogum, who died in August 2017. A local resident from the city’s poor suburbs, he fought for the rights of black people and the LGBT community, of which he was a member, and left a mark on the city. In order to pay homage to him, the students asked their school’s administration to name the building’s meeting area after him. “The directors wouldn’t allow it. Their justification was that none of the school or university’s spaces are named after people. But we did some research and saw that actually, all the spaces were named, but only after white people. So we wondered why Nei couldn’t be honored. Is it because he was poor? Because he was black?” recalls da Conceição.

Despite the school’s refusal, the students’ mobilization didn’t stop. “On the day of our study cycle’s presentation, we screened a documentary about D’Ogum and the teacher held a vote to find out the students’ opinion on the issue. The majority were in favor of naming the space after him,” says de Souza. “It’s another form of resistance. The students are fighting for this cause, and we think it’s a step backwards for the administration not to let us make this tribute,” explains da Conceição.

The confidence and self-esteem displayed by these teenagers is one of the project’s biggest achievements, but there’s more to it. “We can highlight the value given to researching groups as a way of building and ressignifying knowledge, and also the socialization impact of these studies through presentations and publication of the students’ work. Not to mention the students’ realization of the importance of their own leadership in solving problems in their community,” says Roselene Moreira Gomes Pommer, the students’ advisor on the project.

To the teacher, one of the project’s most important effects, which the students also emphasize, is that people learn to honor social and cultural differences among individuals. “In a colonized country like Brazil, the color of your skin, your clothes, your accessories, your religious choices and economic conditions, among other things, can subject you to segregation,” Pommer explains, “but the students have come to see them as elements of distinction and unity. This encourages them to see the world in a their own way, breaking with old preconceptions, and even has an impact on their relationship with their families and the workplace. This reveals the level of leadership and self-determination that they will be able to show when facing the world outside of school.”

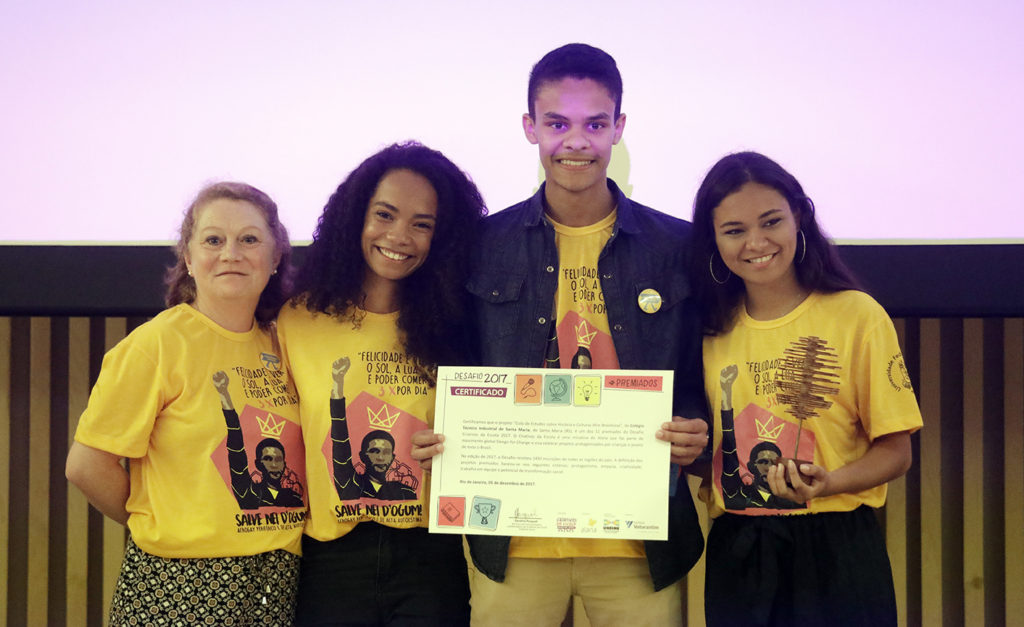

The Ciclo de Estudos sobre História e Culturas Afro-Brasileiras (Study Cycle on Afro-Brazilian History and Cultures) project was one of the winners of the 2017 Design for Change Challenge. Organized by Alana in Brazil, Design for Change encourages children and young people to transform their realities, recognizing them as the protagonists of their own stories of change. The initiative is part of a global movement that started in India and is now present in 65 countries, inspiring over 2.2 million children and youngsters around the world.

Published on 02/27/2018