Erich Kussman dropped out of school when he was 14. Not knowing his father and with a mother addicted to drugs, he spent most of his childhood on the street, armed, selling drugs, and trying to survive. His teenage years were marked by frequent arrests and brief periods of freedom. In 2004, Kussman was involved in a robbery and sentenced to 12 years at the Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility, a prision in New Jersey (United States). Today, at 37, Kussman is married, a stepfather of two and a master’s student at Princeton Theological Seminary. His path from the world of crime to the university started behind bars, with the help of local college students, most of whom grew up with more opportunities than he had.

While incarcerated, Kussman worked in the prison chapel, and in 2008 the chaplain convinced him to take part in a new educational project. “I said, ‘You know what, why not? Let’s give it a shot,’” Kussman recalls. “They don’t really give you too many things to do in prison.”

Kussman joined the pilot group of the Petey Greene Program, which recruits volunteers from universities to tutor prisoners who want to get a high school degree. Founded by two alumni of Princeton University, just a few miles away, that program allowed Kussman, for a year and a half, to receive weekly support from university students. His meetings with those students made him want something different in life.

“At first we didn’t take them that seriously,” he says. “I remember asking a question to one of the tutors. Her name was Julia. And I asked, ‘How much do you get paid for being here?’ And she said, ‘I don’t get paid, I volunteer.’ And that kind of like threw me off a little bit. I’m like, who actually volunteers to come here?” Over time, the dedication he saw in people like Julia inspired him.

“The tutors that were coming in from Petey Greene, they helped me see outside of the box of my own thinking,” says Kussman. “You know, we grow up with certain stigma, certain beliefs, but they were able to transcend those boxes and show me there was life outside of what I know. And that life outside of what I knew was what I started to yearn for and crave,” he said.

With the help of the tutors, Kussman got his high school degree and, once released from prison, went to college. He graduated in biblical studies and soon afterward was admitted to the master’s program at Princeton Theological Seminary. He’s not alone in his accomplishments: at least two former inmates from Kussman’s Petey Greene pilot group now have university diplomas.

The tutoring sessions offered by the Petey Greene Program are weekly, one-on-one, about an hour and a half long and take place in classrooms inside the prisons. Volunteers answer questions about school materials and help students with reading and homework. Sometimes the tutors are called in to teach classes or help teachers. The incarcerated student’s ultimate goal is to pass the exam for the General Equivalency Diploma (GED), which is equivalent to a high school degree. After they pass, the incarcerated students leave the program to make room for other inmates.

Petey Greene Program turns ten with almost 900 volunteers in eight states (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

AT THE BEGINNING, AN ENCOUNTER

Founded by Charles Puttkammer and led by Jim Farrin, both of whom were concerned about the problem of mass incarceration in America, the Petey Greene Program is rooted in the belief that knowledge is essential to the rehabilitation process.

In the 1960s, while working on a program to fight poverty in Washington D.C., Puttkammer met Ralph Waldo “Petey” Greene Jr., a formerly incarcerated person and a skilled communicator who had overcome drug addiction. Greene led a discussion group with ex-inmates undergoing rehabilitation. Says Puttkammer, of meeting Greene, “It was transformative for me, in my life.” The two soon became friends.

With Puttkammer’s encouragement, Greene began to give lectures and make public appearances. Shortly thereafter, he was invited to appear on radio and TV shows and became one of the best-known personalities in Washington D.C. until his death in 1984. Puttkammer, for his part, became more involved in the issue of prison reform, and in 2008 founded the organization that bears his friend’s name. Today, the Petey Greene Program is active in eight U.S. states, with volunteers from 32 universities – including Harvard, Columbia and MIT – offering tutoring in 42 prisons.

Northern State Prison is one of the 42 facilities where Petey Greene Program offers tutoring to inmates (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

This work is important because the U.S. has the largest incarcerated population in the world, with 2.3 million people, or 0.7 percent of its inhabitants, behind bars. These statistics are even more dire when broken out by race. According to the Department of Justice, the rate of imprisonment of black women is almost double that of white women. Black men aged 18 and 19 are 11.8 times more likely to be imprisoned than whites of the same age.

In addition to its startling size, this U.S. prison superpopulation’s schooling levels are much lower than those of their fellow citizens: slightly over 40 percent of inmates have not completed high school, while almost 90 percent of Americans (over 25 years old) have done so. Although there is no federal law requiring U.S. prisons to provide education for inmates, 85 percent of the prisons do. In 2013, a study commissioned by the Justice Department revealed that prisoners who participate in education programs have a recidivism rate 43 percent lower than those who do not.

Elvis Hernandez, who recently passed the GED exam, plans to go to college as soon as he leaves Northern State Prison in New Jersey (which he expects to do this June). “I feel like the things I was doing before weren’t getting me to where I want to go, so I need my education,” he says. At 25, Hernandez did not think he was going to study again after being arrested, but his two sons inspired him to want a better life. He credits the support offered by the Petey Greene Program with his success in getting his GED. “It was an extra help, the tutor helped me and pushed me through the edge, to take my test and pass it,” he says.

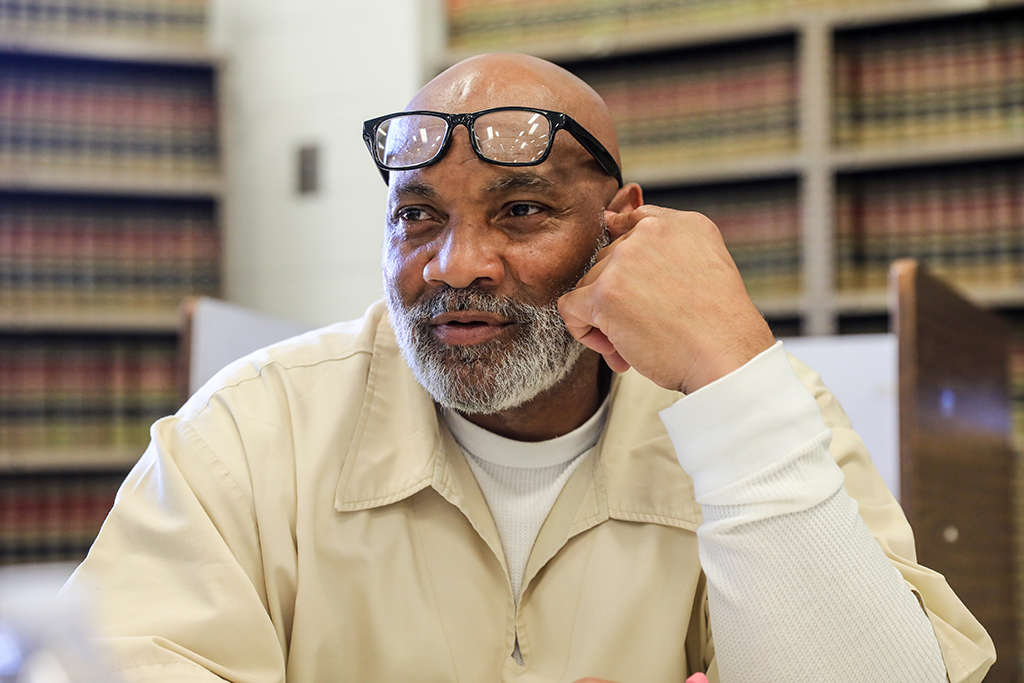

Andrew Rhett, Hernandez’s “classmate” at the prison’s tutoring sessions, left school at 14. After his father’s death, he had to work to help his mother, and became involved in crime. When he was arrested, he did not think studying was necessary. And he didn’t have much confidence in the prison system’s commitment to preparing inmates for life outside. “Here they say ‘rehabilitation,’ and they don’t really rehabilitate you,” says Rhett. “You have to rehabilitate yourself.”

To that end, he sought out the Petey Greene Program after he saw some of its successes: formerly incarcerated friends finishing high school and going to college. Today, at 56, he has changed his mind about education. “Now, my views and my obligations, everything has changed. For the better. And I want to be better, not just for other folks but for me.”

- Andrew Rhett, 56, participates in a tutoring session at Northern State Prison (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

- Inmates Elvis Hernandez and Kevin McCray during a Petey Greene tutoring session (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

- Volunteer Lauren Vazquez explains a lesson to an incarcerated student during a tutoring session (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

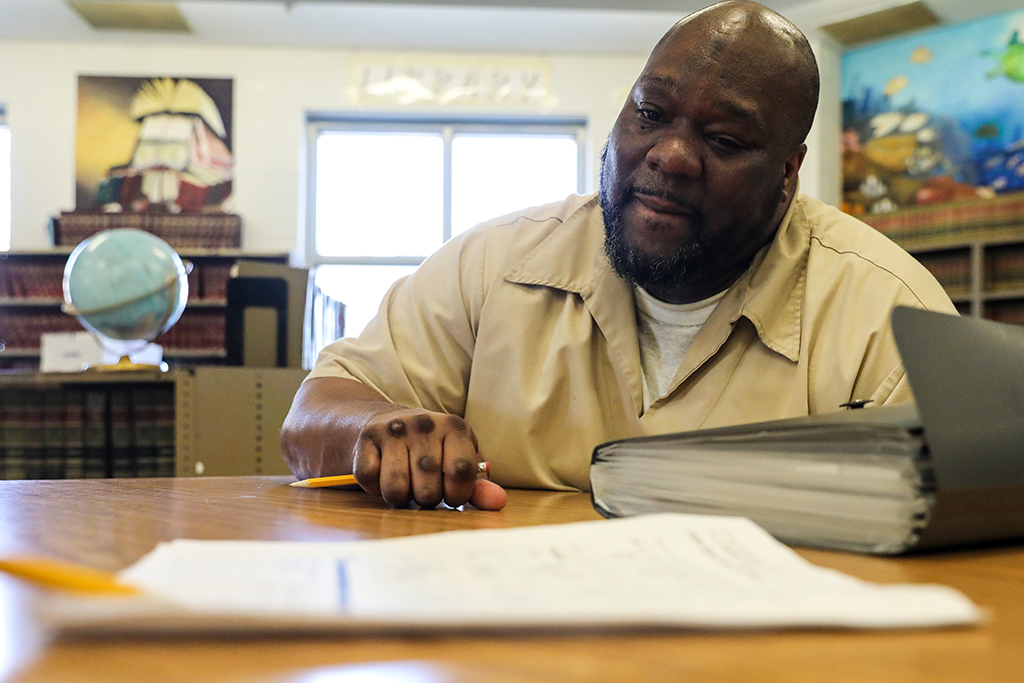

- Charles Brent, 50, participates in a tutoring session at the Northern State Prison (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

- Omar Shepperson during a tutoring session at the Northern State Prison (William Volcov/Believe.Earth)

TWO-WAY TRANSFORMATION

It is not only inmates who benefit from Petey Greene’s tutoring sessions. When they enter the prisons, college students are exposed to a largely unfamiliar world, which often prompts them to confront their prejudices. “[It] was the first time I’d ever been inside a correctional facility, so the one thing I had in my mind was what you see on TV, like the shows that depicted incarcerated people,” says Seda Sahin, a University of Connecticut student who has been volunteering for a year at the Cybulski Community Reintegration Center.

Sahin says she was a little nervous on her first day. But “when I got there it felt like a regular classroom,” she says. “The facility is obviously very different. You know, you can only walk on one side of the hallway, you had to be escorted to the classroom, escorted to the bathroom,” she says.

The sociologist Tony Waters, a professor at California State University, Chico, says the tutoring sessions can be transformative for those on both sides of the bars. “Encounters between prisoners and college students are important for both the inmates and the students,” he says. “Students need to see how prisons work, and any contact that the prisoner has with people on the outside is a good thing.”

Karen Shen, a doctoral student in economics at Harvard and who has been volunteering in a women’s prison for three years, says the experience has made her a better teacher. “I think it has made me hopefully a lot more able to empathize with somebody who either doesn’t feel like doing their homework on a particular day or doesn’t feel confident about their ability to do homework on a particular day,” she says.

Montclair State student Sam Mompoint, who has been volunteering for six months, has a similar perception. “I want to make sure that whoever I am helping, at whatever level it is, that they are getting the best quality support and teaching that everyone deserves,” he says. “[Mass incarceration] has hurt our community. I’m black, and it’s hit us in a lot of ways.” Incarceration has “taken a lot of people who could have done so many things for the community,” he says. “And I like the feeling of being able to be helpful.”

This exchange seems to be one of the key ingredients in the program’s success. “We learn from them and they learn from us. So it’s a two-way street,” says Andrew Rhett. “We need more of them to come in, to pick up the pieces and help us to start our lives again.”

Published on 05/10/2018