The idea was to plant trees along 8,000 kilometers (4, 970 miles) to build a Great Green Wall from coast to coast across the African continent, spanning 11 countries along the Sahara Desert, a distance as long as that between Rio de Janeiro and New York City. (The project is named for a similar and much older effort in China.) But the plan to build a huge forest, to help restore the soil and native vegetation of a region that suffers from desertification, has changed since its 2007 beginnings. No longer just an environmental project, Africa’s Great Green Wall has become a social one.

Leaders and experts from 20 countries supporting the Wall realized that it would be better to engage rural residents and learn from their wisdom instead of reforesting on their own at the risk of losing all investment. “One of the key strengths of the Green Wall today is developing the skills and abilities of local communities so they can be agents of change,” Nora Berrahmouni told Believe.Earth. Berrahmouni is the director of Action Against Desertification, a project of FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), the UN food and agriculture agency. “Communities are the ones deciding which trees or shrubs they will plant or protect, and which initiatives will be put into practice.” The goal is to get residents to plant on their lands, generating income and keeping their children in school without being forced to migrate to cities, or to other countries.

The Green Wall’s initiatives are aimed at empowering villagers, especially women (Photo: UNCCD)

One of the techniques valued in the program and used in Burkina Faso is called zai, in which farmers dig a 15-centimeter (5.9 inches) hole in which they put fertilizer, composting soil and seeds. This underground mixture, bolstered by stones, retains rainwater and provides a reservoir of moisture when drought comes. The country also invested in the planting of shea, a traditional African fruit whose nuts are the main ingredient in a butter widely used in cosmetics.

Senegal chose to increase tourism by reintroducing animals that had disappeared from its landscape. A 2014 survey of 148 tour operators in Africa found that wildlife-watching accounted for 80 percent of trip sales.

In Niger, a technique called assisted natural regeneration (ANR) is working well. ANR emphasizes the protection of seedlings, as well as the pruning of extra shrub branches to give plants the strength to grow and to produce fruits and fodder for cattle, in addition to fertilizer for the land. People in Niger also chose to plant acacias, trees that lose their leaves in the rainy season, thus fertilizing the soil for the next season. These trees also generate income as gum arabic can be extracted from their bark. “Planting crops among trees was a practice of the Sahel people [Sahel is a region between the Sahara and the fertile lands located in the south], but it was left behind when French settlers convinced the locals that the land needed to be cleared before planting and that gardens and trees should be separated,” says environmental consultant Arouna Campaore, who lives in Tera, Niger. “But without the protection of trees, the soil dries up and becomes unproductive.”

Soil recovered in Niger, allowing people to plant and generate income, reducing poverty and migration (Giulio Napolitano/FAO)

DIVERSITY VALUE

The great wall became a huge mosaic of green, bringing social and environmental abundance. It has already restored 15 million hectares (more than 37 million acres) of degraded land in Ethiopia, planted 11.4 million trees in Senegal and created 20,000 jobs in Nigeria. By 2030, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) aims to restore 10 million hectares (24.7 million acres) of degraded land annually and create 350,000 jobs in rural areas.

The initiatives range from microcredit to training locals in sustainable techniques to investing in machinery for agriculture. Many of the ideas generated in the villages are replicated in other communities as their success spreads by word of mouth.

The introduction of tractors has recently improved life for women in Burkina Faso and Niger. “In the beginning, they used to work manually in heat of up to 45°C (113°F),” says the FAO’s Nora Berrahmouni. “Now, they can go to work with fewer physical demands, which is good for their health.” Women also receive support to develop agroforestry and grow food for their households’ consumption. “I was surprised by the results appearing in the first year,” says Arouna Campaore. “And, what most impresses me is knowing that 80 percent of the beneficiaries are women. Now, they have sources of income, such as selling the seeds.”

- Senegal is one of the five countries benefitting from a project funded by the European Commission (Photo: UNCCD)

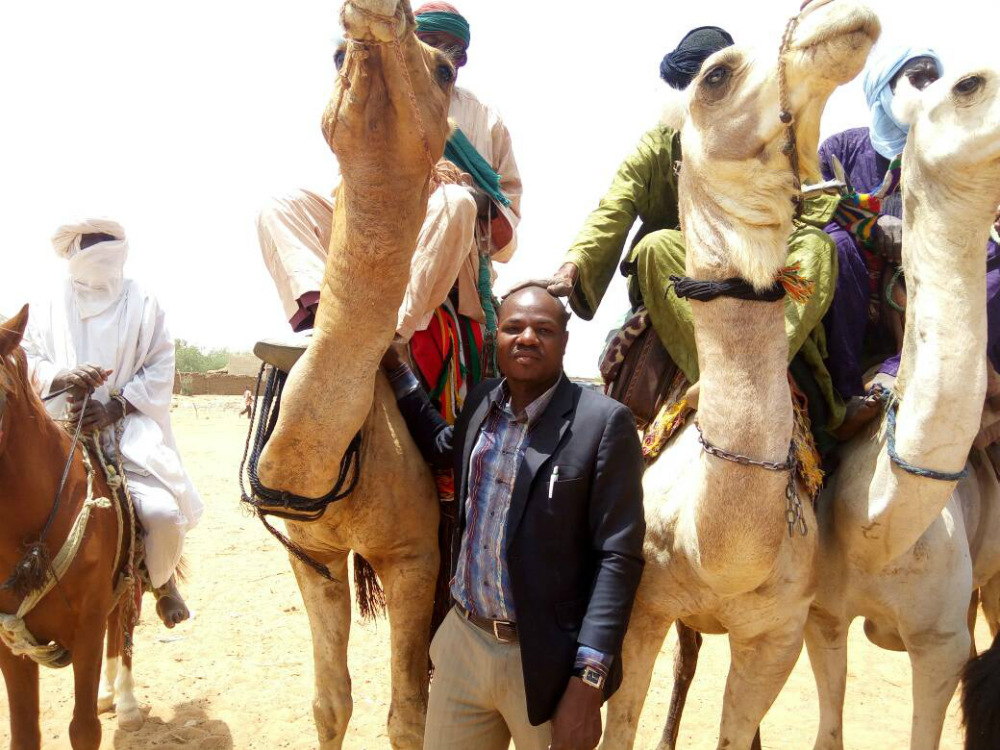

- Arouna Campaore, an environmental consultant in Niger who works in the same region where he grew up, says the program has been quick to show results (Campaore’s Personal Archive)

- In Niger, women prepare the soil in heat that reaches 45°C (113°F) (Giulio Napolitano/FAO)

Dozens of institutions form the US$8 billion funding base supporting the programs of the Great Green Wall, such as the World Bank, the European Commission and FAO. Other UN agencies, such as the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) are also involved.

The support of the private sector has been growing through partnerships that allow trade in products such as gum arabic. “We have to increase investment and effort as lots of time has been lost in bureaucracy. Now, we need to expand the project, definitely,” says Berrahmouni. “Due to difficulties brought about by climate change, poverty and armed conflict, we cannot slow down. It’s a race against the clock.”

Another challenge is population growth. Today, Sahel has 135 million residents. By 2050, that number will surpass 300 million people. “If we work with nature even in challenging places like Sahel, we can overcome any adversity and build a better world,” says Berrahmouni.