Peruvian entrepreneur Boris Gamarra, 29, was the first member of his family to receive a university degree. He studied economics at Peru’s largest public university, the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

“More than 80 percent of my classmates were part of D and E socioeconomic classes,” Gamarra told Believe.Earth, referring to the lowest and second-lowest levels on Peru’s official income scale.

“So was I. We were all the only ones among our relatives who had studied at a university.”

Gamarra grew up in Buenos Aires de Villa, in Lima’s Chorrillos district, an area whose residents recently had problems with gang activity. But, upbringing was not the only connection between him and his classmates. They all also shared the goal of studying economics and using it to help tackle Peru’s widespread poverty.

For some, it was just a fantasy. But, Gamarra has tried to make good on his idealism. In 2015, he created a business, Recidar, that collects clothes and household items from companies and families, then sells them at reduced prices to people who can’t afford to shop in supermarkets or at department stores.

Clothes are the best seller at Recidar. Ornaments and decorations do second-best (Audrey Córdova / Believe.Earth)

“Second-hand markets in Lima are usually informal and unhealthy,” said Gamarra, “But the main problem is that most of them deal in stolen goods. When you buy there, you’re nourishing the cycle of violence without even knowing it. We are fighting crime, though our clients might not see us that way.”

RECEIVING AND RECYCLING

Gamarra took part in several other sustainability projects before founding Recidar. When he was a student, he and his friends created an initiative to collect donations to then give to poor people.

After that, he worked at a nonprofit specializing in recycling.

“In Lima,” he said, “just the 4 percent of solid waste is reused.”

Gamarra worked as a recycling trainer, teaching company employees around Lima about proper recycling practices.

“My uncle lent me a truck,” he said. “We’d collect the recyclables and sell them. With the money we made, we organized 20 donation drives for books and clothing, all around the country.”

When they visited the companies’ offices, they also collected second-hand items employees brought in. Boris didn’t charge people for them. He just gave them away to whoever needed them.

Many of Recidar’s clients are mothers who are also heads of their households (Audrey Córdova / Believe.Earth)

A DREAM OF CHANGE

Gamarra’s first project, collecting donations for the poor, was enough to win him a competition in 2014 held by the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Center at the Universidad del Pacifico, in Lima. The prize was the advice of experts who would help him transform his project into a proper social enterprise.

“We did a financial analysis of my operation and we discovered it wasn’t making much progress,” Gamarra said. “So, we repositioned the activity. Our aim was sustainability, scalability and replicability.”

Later the same year, Gamarra spoke at the Climate Summit (COP 20) in Lima. Soon after, Recidar won another Universidad del Pacifico competition.

“New doors opened at that stage,” he said. “Our network of contacts broadened.”

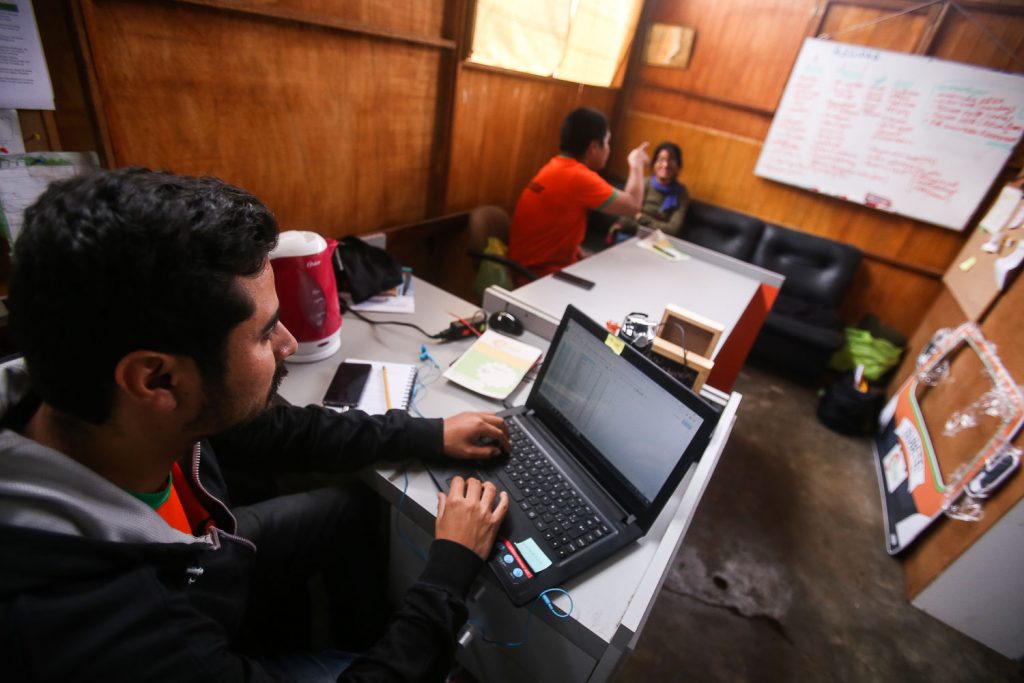

Recidar makes its home in a rented, 700-square-meter office. The office furniture is second hand, from corporate donations (Audrey Córdova / Believe.Earth)

In 2015, yet another competition win brought Gamarra to Incae Business School, in Nicaragua, where he met several prominent social entrepreneurs. One of them was Joaquín Leguía, director of the Peruvian nonprofit Asociación para la Niñez y el Medio Ambiente (Ania), the Association for Children and the Environment.

“I am lucky that I can count on him to help and answer my questions,” said Gamarra. “Leguia is my main role model nowadays, like a new father figure. My mother raised me. We received economic support, but I did not have a father who counseled me. Rather, I had a father who betrayed my mom.”

Gamarra’s most important support, though, comes from wife Liseth, he said.

“She is the one who believes in me,” said Gamarra.

A SHARED PASSION

Gamarra’s partner in Recidar, Luis Miguel Pazos, manages marketing and innovation. The two men share a conviction that they can change people’s lives. Now, their aim is to help the rest of their team devote themselves into the cause and to develop a plan to help the communities where their customers live.

They’re especially concerned about women.

“The main challenges the women face are, one, to get food every day and, two, to find a way to avoid being beaten by their husbands,” Gamarra said. “The environmental issue remains in the background in that scenario. That is why we used to say that we give access to products, but we have not yet made anything that breaks the poverty cycle and empowers women.”

Gamarra (right) with Luis Miguel Pazos, his partner in Recidar (Audrey Córdova / Believe.Earth)

More than 30,000 families have donated to or bought products from Recidar, and the company has 30 other businesses as partners.

“We try to make our customers feel that they are not recipients of assistentialism. We’re not interested in assistentialism,” Pazos, who recently completed a master’s degree in social innovation at Amani Institute in Kenya, told Believe.Earth, referring to the practice of offering never-ending handouts to poor people, often contrasted with efforts to empower them.

“All of Recidar’s salespeople wear uniforms. We instruct them to be warm and gentle and to mind their appearance. We have a customer service protocol. We try to keep a nice store, a tidy store, because we want to sell dignity—and that starts with the way we present the products and the shopping experience.”

Gamerra and Pazos want to inspire more and more young people to choose the path of the social entrepreneurship and to act as social change agents in the businesses where they work and in the neighborhood they live.

“That’s how we build the country we dream of, the country we deserve,” said Pazos, “by becoming the change we want to see in the world.”