After attending his first week of classes in the city, Anderson Silva, 21, was coming back home. He jumped on his motorcycle, and on the way to his land in Ribeirão, he began to observe the landscape, as if for the first time. It was not new to him; after all, he had been born and raised there. But his perspective had changed. “I looked at the fields and said, ‘Wow, this is a very nice place to live! How can I think of moving from a natural landscape like this, to an urban one that has nothing to do with me?’ Since then, I have set a goal for my life: I intend to dedicate myself to the place where I grew up.”

Silva lives in the rural part of Glória do Goitá, 63 kilometers from Recife (the capital of Pernambuco, Brazil). He is a son, grandson and great-grandson of farmers. On his family’s property, he learned how to use the hoe at the age of six, and to plant and reap. He was supposed to inherit the land of 1 hectare (2.47 acres); this was supposed to be his future. As he grew up, he began to chafe at that predetermined future.

“Although I’ve lived in the countryside for all my life, I thought it was not for me,” he says. “When I started studying, the teachers used to encourage us to seek ‘a better life than our parents had’. So, my idea was to finish high school and move to the city.”

He and his family are part of a minority who still lives in the countryside: three out of four Brazilians live in cities, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). There was a massive urban migration in the 1950s. While cities were associated with progress and opportunity, the countryside, on the other hand, for young people like Silva, represented poverty and provincialism.

Brazil’s 2010 Census found that the number of people aged 15-24 in the nation’s rural areas had, over a decade, declined by 10 percent. As a result, Brazil’s rural population has grown old. In 2006, people aged 25-35 accounted for 13.5 percent of those living in the countryside; today, they do not reach 9.5 percent.

Anderson Silva was ready to be part of this rural depopulation trend. Motivated by professional aspirations, he started a technical course in agroecology at the Service of Alternative Technology (Serta). Only a week of classes in the city of Glória do Goitá was enough for him to find something he had lacked: perspective on his life.

THE FARMER’S VALUE

Serta is now unofficially dedicated to promoting farmers’ self-esteem. The organization was founded in 1989 by technicians and educators working for the Center for Training and Alternative Projects (Cecapas). “We noticed that the farmers’ work was impaired by the school,” says Serta’s founder, Abdalaziz de Moura. “It was common for teachers to say to a student, ‘You’d better study, otherwise you will end up like your father — with a hoe in your hands.’ The school used to teach that the countryside was underdeveloped and lived in the past compared to the city. But, we didn’t accept that, and we worked to address the problem.”

To change this way of thinking, Serta created a new approach based on popular education, and called it Educational Project to Support Sustainable Development (Peads), with the intent that the students be the ones who change their own reality. The first Peads program, in local development, graduated six classes after a year and a half of coursework.

Since 2010, Serta has also provided a technical program in agroecology — also a year and a half long — which has already trained 1,800 people. Students spend a week living in one of the two Serta campuses, in the cities of Glória do Goitá and Ibimirim, Pernambuco. Then, they go back home and use what they’ve learned on their own land. “We believe in a kind of education in which school and community are one single element together with our bioma,” says educator Sebastião Alves, director of Serta. “Along these lines, we have helped transform the perspective in the field.” Highlighting the potential and wealth of the region’s semi-arid land, Serta has helped to reduce the migration rate of its students to cities.

Sebastião Alves, best known as Tião, specializes in training students to maximize the potential of the fields. (Rafael Martins/Believe.Earth)

“At no time can the city offer similar conditions,” says Alves. “In the countryside, with a piece of land, you can work, produce, manage and feed your family. The problem is education. How can we find solutions for our problems if we do not have formal knowledge?”

Brazil has 15 million rural workers, 1.5 million less than in 2006, according to the IBGE. In 2006, family farming was the economic base of 90 percent of the municipalities with 20,000 or fewer inhabitants. Valuing and supporting the small farmer in the countryside helps local social development and cultural preservation, in addition to mitigating the population growth of large cities. It is also a way of guaranteeing the quality of everyone’s food.

Serta operates in 121 cities in six states and has set a national standard for rural schools. Since 2016, it has been part of Ashoka’s Transforming Schools program, which brings together social entrepreneurs in 34 countries who are education innovators.

“The Transforming Schools program is based on some ideas, such as teamwork, empathy, and the centrality of the students. These are not only a part of the curriculum, but organizing principles,” says Serta’s president, Germano Ferreira. “We do not graduate students to look for a job outside of their community. Instead we prepare them to use what they’ve learned in their community.” In 2018, Serta’s programs became state-funded in Pernambuco. The next step is to become part of the university system.

Women began to discuss their role in agriculture once they started taking classes at Serta (Rafael Martins/Believe.Earth)

Fabiana Gomes, 27, a native of the Kambiwá people, was introduced to Serta when she was trying to leave the village in the Sertão do Moxotó, Pernambuco, where she’s spent her whole life. She was studying to be a teacher and was looking for additional training when a neighbor told her about Serta’s programs. She graduated from Serta in 2016. “It was a special key that opened a huge door of possibilities for us,” says Gomes. “A physical and mental transformation.”

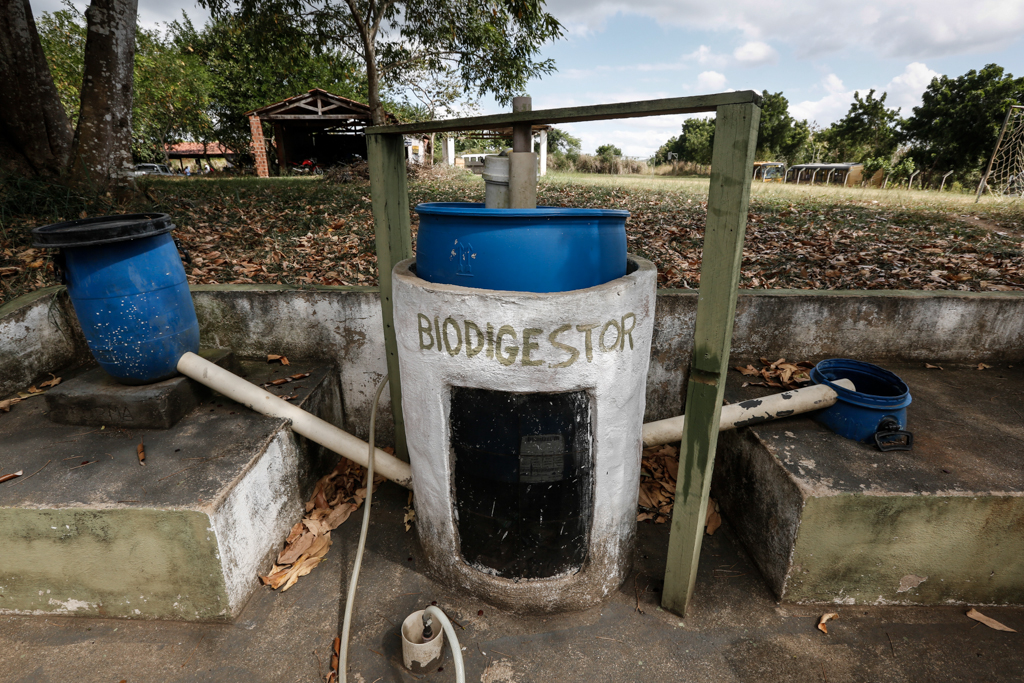

Gomes gave up the idea of moving to the city. She now helps train other technicians as a field educator with Serta. Most students want to look after — and develop — their own land. “I pass along what I’ve learned about the technologies,” Gomes says, describing some of the sustainable practices she teaches from her own life. She has installed equipment that treats the water in her sink before returning it to nature. “I’ve made a windbreaker out of plastic bottles, a compost, and a rooftop vegetable garden. I make biofertilizer from animal bones,” she says.

- Fabiana Gomes made up her mind and decided to stay in her village, in Inajá, in southern Brazil, becoming an educator at Serta (Rafael Martins/Believe.Earth)

- Students spend a week living together at Serta, then bring the lessons back home (Rafael Martins/Believe.Earth)

- Graduation of farmers after a year and a half of studying agroecology at Serta (Rafael Martins/Believe.Earth)

- During class, students learn how to make a biodigestor, a hanging vegetable garden, a water treatment system and other sustainable technologies (Rafael Martins/Believe.Earth)

ANDERSON’S ACHIEVEMENT

When Anderson Silva got home after his first week of classes, he began to think about the land where he’d lived and planted all his life. Although 70 percent of food that the Brazilian population eats comes from family agriculture, Silva’s family consumed none of what they planted. They used to sell all the production and go to markets to buy their own food. They brought everything home in plastic bags, which they then threw around the house — and the property. When Silva got home from school, his father was planting corn in the midst of this white plastic heap.

“I’ve lived my whole life in the country and thought I knew everything about it,” says Silva. “But, when I was introduced to Serta, I discovered this wasn’t true. I had the basic knowledge, but lots I needed to learn. I was living in the countryside, but I didn’t live in balance with nature. So, I needed to rethink and rebuild all my knowledge. The first thing to do was to collect the plastic bags littering our land. It took me a week to fill 25 bags of waste.” Anderson prepared a presentation on the subject for his classmates at Serta. People loved it!

“I thought the countryside was a place of poor people and hard work, that I wouldn’t be able to be someone living here,” he says. “But, I’ve learned a lot at Serta. One of the most important things was to raise my self-esteem. I learned that I’m responsible for changing my own reality.” His goal is to make his land in Ribeirão a fully agroecological property, producing no waste. Young people like Anderson Silva are change agents who can secure the sustainable future of agriculture.

Published on 10/15/2018